All my life I’ve been fascinated by the fact that there is no unequivocal truth. The challenge for me as a filmmaker is to reveal the complexity of this theme by exposing parallel worlds where different truths live side by side. In the winter of 1990, shortly after the fall of the Berlin wall, I travelled to St. Petersburg - then still called Leningrad - for the first time. I was gripped by the silent revolution taking place there and started closely following the development of Russia and its inhabitants.

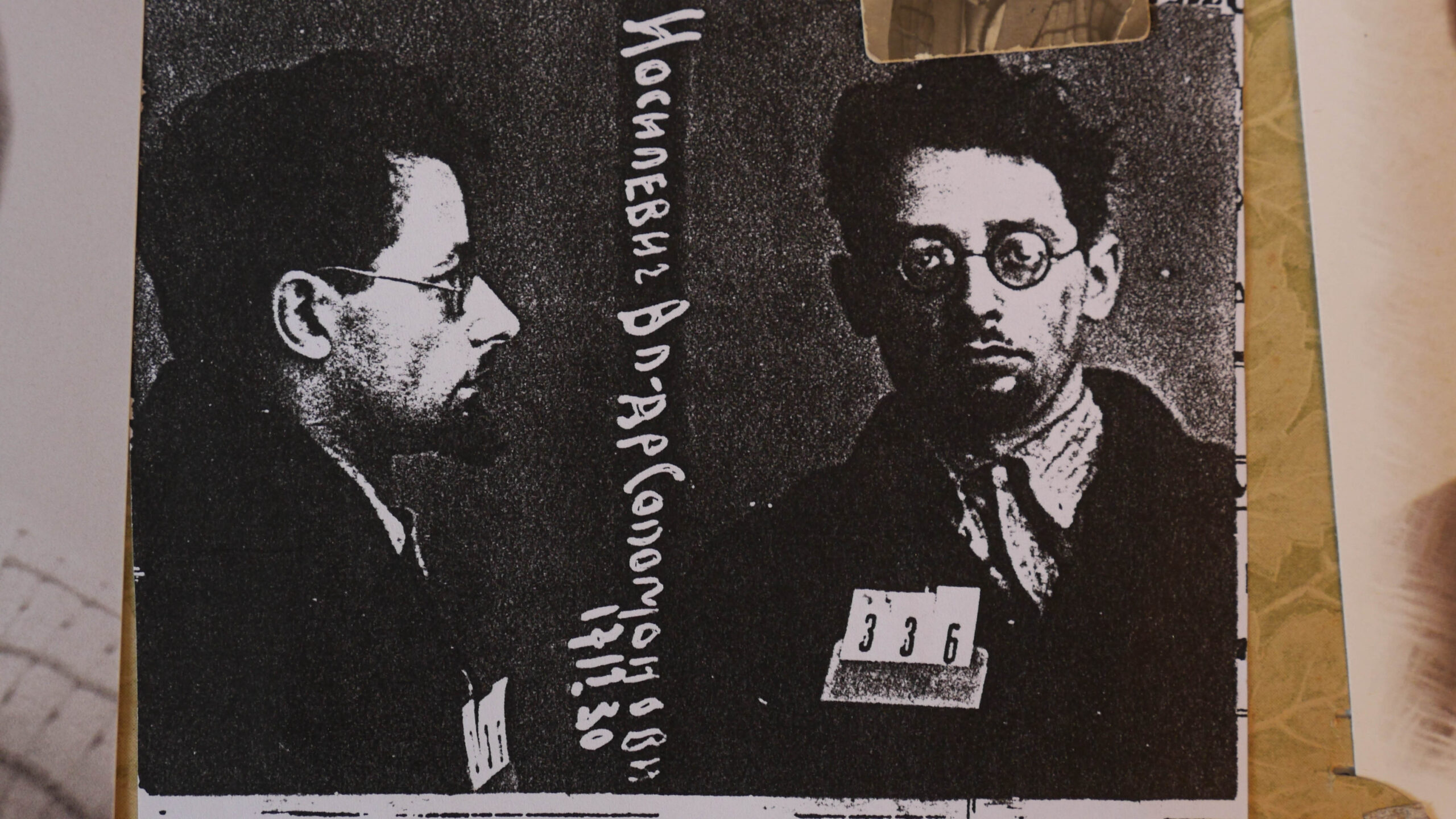

I am struck by the way Russians deal with their extremely painful collective past. How do you get your head around the fact that the man you have pinned all your hopes on to lead you to a glorious future is the same man who abandons his own people and has them killed randomly? Surely this violent history that took place during Stalin’s regime, in which hardly any family escaped the killings, must have left deep marks in the lives of current generations? Then why is this history apparently not an issue in today’s Russia?

For this film, as I did for my previous film, 900 Days, about the myth and reality of the Siege of Leningrad, I talked to “ordinary” Russians: young, old, people from the city, from the country, from all walks of life. In The Red Soul they reveal how difficult, delicate and painful a subject this extremely violent past is to them; how they deal with it, what place it occupies in their lives and how different their perspectives are on this history.

The wiping out of independent farmers in order to realize the Communist ideal of collectivization, Stalin’s terror followed by World War II leading to millions of victims – not a single Russian was left unaffected. This succession of cruel events took place without being followed by any sustained period of quiet and economic stability. The chaotic 1990s that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union turned out to be yet another traumatic experience for many Russians. The “promised” freedom came with a callous capitalist system in which many were unable to keep their heads above water, giving them no time or space whatsoever to reflect on and come to terms with what had happened in the past.

In The Red Soul I not only show how the first generation deals with these traumas, but also the way it influences the next generations and how this affects today’s Russia. The different realities of their history as outlined by Russians often clash with my own vision, my Western perspective in which crime should naturally lead to punishment. To understand today’s Russia in which Stalin seems to be restored to his pedestal, it is important to take these different, paradoxical and coexistent interpretations of Soviet history seriously, rather than holding on to a single vision.

It’s the personal stories that bring us closest to individual people and give us insight into the big historical picture. Different perspectives together offer a view of history that is at least as interesting as one official line. The main insight I gained in making this film is that emotional repression can be a necessary survival strategy. When these different perspectives, or in this case realities, exist within one generation, one family or even one person, it may not make history any easier, but it does make it more intriguing.

![]() .

.![]()

![]()

![]()